This series is about my investigation of a mail fraud ring that attempted to scam my firm, the history of its bad actors, and the methodology that I used to look into it. You can see the whole chapter index here.

More than seven years ago, I became irritated at a fraudster trying to scam my office and started to write about him. Seven years and fifteen posts later, the slow-grinding wheels have ground their last on the case. Earlier this week, David Bell — the central figure of this Anatomy of a Scam series — was sentenced to 108 months in federal prison after his guilty plea to mail fraud and wire fraud. There's no parole in the federal system any more; Bell will do at least 85% of that time, or about seven and a half years. He'll be on "supervised release" — the modern federal equivalent of supervised parole — for three years after that, and will be at risk of being sent back to prison if he's caught engaged in fraud again. He's scheduled to surrender in March.

This is not a typical result. There are tens or hundreds of thousands of con artists out there, and they frequently escape detection. When they are detected, they frequently escape prosecution, and when they are prosecuted, they frequently escape with mild sentences on lesser charges, leaving them free to victimize again. This sort of hard-time outcome is rare despite the amount of harm these people inflict. The government simply doesn't have the resources to mount this sort of investigation against any but the worst of the worst.

But I don't want readers to take that grim message away from this series. Rather, I want people to see that they can take initiative themselves — that they can use the techniques and research tools I've discussed in this series to track down the people trying to scam them, to spread the word about them, and to inform law enforcement about them. The best defense against con artists isn't the government, because government doesn't have the resources. The best defense is self-reliance, healthy skepticism, involved communities, and public-spirited private investigation that can be broadcast far and wide through modern tools.

Copyright 2017 by the named Popehat author.

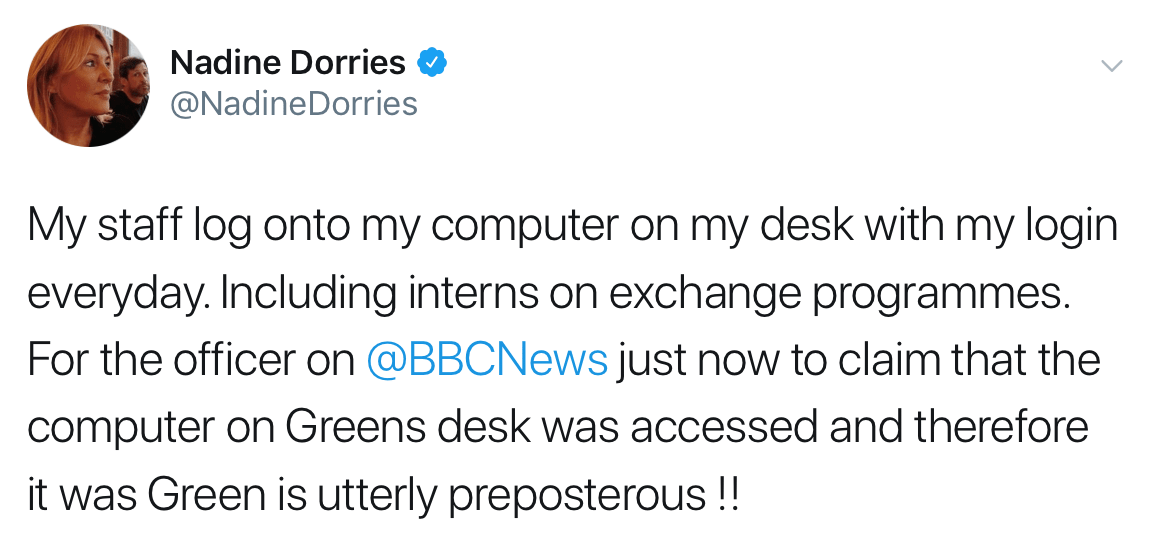

Yesterday I had a bunch of people point me at a tweet from a politician in the UK named Nadine Dorries. As it turns out, some folks were rather alarmed about her position on sharing what we would normally consider to be a secret. In this case, that secret is her password and, well, just read it:

My staff log onto my computer on my desk with my login everyday. Including interns on exchange programmes. For the officer on @BBCNews just now to claim that the computer on Greens desk was accessed and therefore it was Green is utterly preposterous !!

— Nadine Dorries (@NadineDorries) December 2, 2017

For context, the back story to this is that another British pollie (Damian Green) is presently in hot water for allegedly accessing porn on his gov PC and Nadine is implying it could have been someone else on his PC using his identity. I read this while wandering around in LA on my way home from sitting in front of US Congress and explaining security principles to a government so it felt like a timely opportunity to share my own view on the matter:

This illustrates a fundamental lack of privacy and security education. All the subsequent reasons given for why it’s necessary have technology solutions which provide traceability back to individual, identifiable users. https://t.co/xSOreDnD62

— Troy Hunt (@troyhunt) December 2, 2017

And that would have pretty much been the end of it... but the topic kept coming up. More and more people pointed me to Nadine's tweet and the BBC also picked it up and quoted me. As I dug into her tweets (and those supporting her) while waiting for my bags back home in Australia, it became apparent this was becoming somewhat of a larger issue. I wanted to lay things out in a more cohesive fashion than tweets permit, which brings us to this post.

Other People Sharing Credentials

To be fair to Nadine, she's certainly not the only one handing her password out to other people. Reading through hundreds of tweets on the matter, there's a defence of "yeah but others do it too":

I certainly do. In fact I often forget my password and have to ask my staff what it is.

— Nick Boles MP (@NickBoles) December 3, 2017

It is extremely common for MPs to share their parliamentary login details with their staff. Seems slightly unfair to vilify @NadineDorries for what is common practice

— JamesClayton (@JamesClayton5) December 3, 2017

I seem to have started a hare running. As an MP I employ 4 people to deal with the emails and letters constituents send me. They need access to these communications to do their jobs. No one else has access. Passwords are regularly changed.

— Nick Boles MP (@NickBoles) December 3, 2017

Firstly, that's not something I'd advise announcing in public because as you'll see a little later, admitting to that practice could have some rather severe consequences.

Secondly, the premise of justifying a bad practice purely on the basis of it being common is extremely worrying. It's normalising a behaviour that we should be actively working towards turning around. Particularly when we're talking about public figures in positions of influence, we need to see leadership around infosec, not acknowledgement that elected representatives are consciously exercising poor password hygiene.

What's the Problem Credential Sharing is Solving?

Let's start here because it's important to acknowledge that there's a reason Nadine (and others) are deliberately sharing their passwords with other people. If we can't get to grips with the root cause then we're not going to be able to effectively talk about the solutions.

Reading through the trove of tweets that followed, Nadine's challenge appears to be handling large volumes of email:

You don’t have a team of 4-6 staff answering the 300 emails you receive every day

— Nadine Dorries (@NadineDorries) December 2, 2017

Let's be sympathetic to the challenge here - answering 300 emails a day would be a mammoth task and the principle of sourcing help from staffers is a perfectly reasonable one. Her approach to password sharing may simply be evidence of humans working around technology constraints:

I don't blame her, I blame the I.T dept for not managing this risk adequately. It isn't up to her to have to defend this. She has a valid business need and I.t needs to meet this need and be secure also. I. T is the group that should be explaining themselves, not her

— Matthew Petersen (@PetersenMatthew) December 3, 2017

I totally agree with the premise of technology needing to meet business requirements so let's take a look at how it does precisely that.

Understanding Delegated Access

As many people pointed out, there are indeed technology solutions available to solve this problem:

Have these people never heard of delegation permission?

— raoul (@raoulendres) December 3, 2017

and that is precisely why email is capable of forwarding messages as well as delegating access to *separate* individual accounts.

— Chris Vickery (@VickerySec) December 4, 2017

There is no need to share your password for them to access your email. Your password is your password and needs to stay that way for accountability. Email delegation is easily set up by your I.T. team.

— FamilyofFlowers (@FamilyoFlowers) December 4, 2017

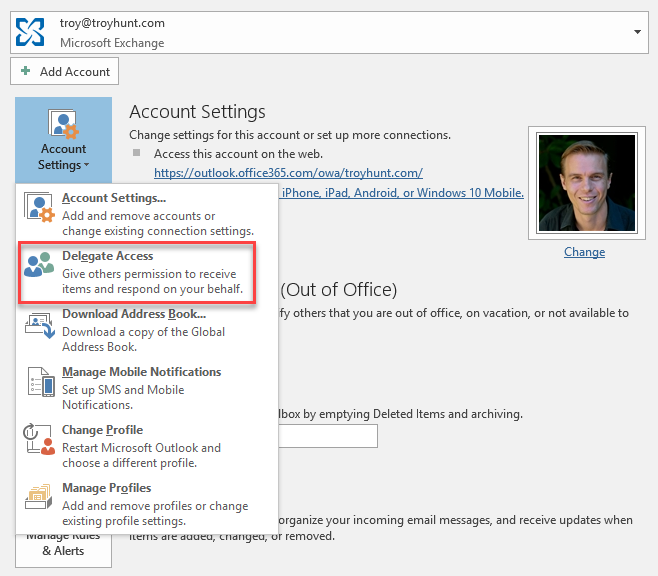

The concept of delegation hinges on someone else being able to perform duties on your behalf. How this is done depends on the technology of choice, for example in the Microsoft world there are a couple of ways to grant other people access. Firstly, you can share folders such that another party can access your mail. Now that's not strictly delegation (they can't act on your behalf), but it addresses use cases where someone else may need to access your messages (i.e. a personal assistant).

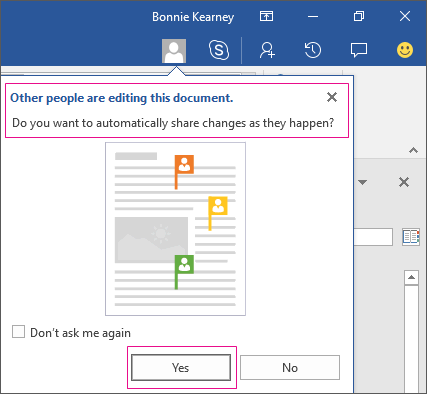

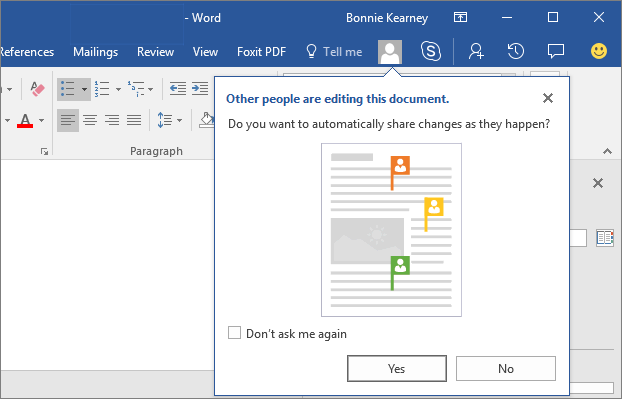

In order to truly delegate access to someone else, it only takes a few clicks:

It's certainly not a concept unique to Microsoft either, it's actually a very well-established technology pattern to address precisely the scenario Nadine outlined above.

Other Collaborative Solutions

Let's not limit this discussion to just providing access to email though, there were other scenarios raised which may cause people to behave in a similar way to Nadine:

Have you tried to have group editing of a document using multiple logins? It is hard enough with source code, try making Word do that. Standard IT does not support the concept of group work.

— Picaro Byte (@__picaro8) December 3, 2017

If you want to secure it, point a security camera at the console.

I really hope the suggestion of a security camera was tongue in cheek, although admittedly I did chuckle at the irony of this being a potential solution to regain the ability to identify users after consciously circumventing security controls!

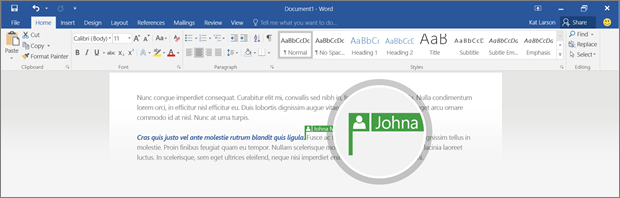

But in answer to Picaro's question, yes, I have worked with a group of people all editing a document under separate identities. Products like SharePoint are designed to do precisely that and by their very nature are collaboration tools. If the logistics of this sounds confusing, check out the guidance around collaborating on Word documents with real-time co-authoring. Pictures speak a thousand words here:

But again, this is far from being just a Microsoft construct and many readers here would have used Google Docs in the past which is also excellent for working collaboratively on content under unique identities. This is far from an unsolved technology problem. Indeed, the entire premise of many people within an organisation requiring access to common resources is an age-old requirement which has been solved many different ways by many different companies. There's certainly no lack of solutions here.

Identity, Accountability and Plausible Deniability

One of the constant themes that came back to me via Twitter was "plausible deniability":

“Plausible deniability” was not named, but my first thought. Traceability back to individual users == surveillance, authoritarian IMHO.

— Jan Wildeboer (@jwildeboer) December 3, 2017

Plausible deniability is probably more convenient to those involved, than actual security.

— Luke Van In (@lukevanin) December 3, 2017

Many others also suggested precisely this in replies to Nadine so let's look at exactly what's meant by the term:

Plausible deniability is the ability of people (typically senior officials in a formal or informal chain of command) to deny knowledge of or responsibility for any damnable actions committed by others in an organizational hierarchy because of a lack of evidence that can confirm their participation, even if they were personally involved in or at least willfully ignorant of the actions

The assertion here is that someone in her position could potentially say "something bad happened under my account but because multiple people use it, maybe it was someone else". The thing is, this is precisely the antithesis of identity and accountability and if this is actually a desirable state, then frankly there's much bigger problems at hand.

The situation with Damian Green trying to explain his way out of porn being on his machine perfectly illustrates the problem. The aforementioned BBC article contains a video where he says:

It is the truth that I didn't download or look at pornography on my computer

Yet - allegedly - pornography was found on his machine. The plausible deniability Nadine alludes to in her tweet is that how do you know it was him that downloaded it? I mean if many different people have the ability to operate under Damian's identity, that porn could have been downloaded by any number of people, right? Giving someone else access to your account leaves the door open to shirking responsibility when things go wrong.

The Ramifications of Providing Credentials to Other People

Here's an argument I've heard many times in the past:

You need a pass to get that. Everyone who has my login has a security pass.

— Nadine Dorries (@NadineDorries) December 2, 2017

The assertion here is that other people are already in positions of trust and as such, excessive permissions aren't a problem as you can rely on them to do the right thing. There are two fundamental flaws with this:

Firstly, there are plenty of people in positions of trust who haven't done the right thing. The most impactful example of this is Edward Snowden persuading NSA colleagues to provide their credentials to him. Now regardless of whether you do or don't support what Ed then did with those credentials, the point is that he was in a position where those around him trusted him - he had a security pass! You'll find many other examples ranging from system admins going rogue to insiders pilfering corporate documents for profit to the guy who outsourced his job to China so he could watch cat videos. Just because you trust them isn't sufficient reason to give them any more rights than they require to do their job.

Secondly, there are plenty of people who unwittingly put an organisation at risk due to having rights to things they simply don't need. I often hear an anecdote from a friend of mine in the industry where a manager he once knew demanded the same access rights as his subordinates because "I can tell them what to do anyway". That all unravelled in spectacular style when his teenage son jumped onto his machine one day and nuked a bunch of resources totally outside the scope of what the manager ever actually needed. We call the antidote for this the principle of least privilege and those inadvertent risks range from the example above to someone being infected with malware to phishing attacks. There's not necessary malice involved on behalf of the person with "a security pass", but the unnecessary trust placed in them heightens the risk.

In fact, social engineering is especially concerning in an environment where the sharing of credentials is the norm. When you condition people to treating secrets as no longer being secret but rather something you share with someone else that can establish sufficient trust, you open up a Pandora's box of possible problems because creating a veneer of authenticity in order to gain trust is precisely what phishers are so good at! Imagine an intern (per Nadine's original tweet) being asked for a password by someone posing as the boss in an environment where requesting this is the norm. You can see the problem.

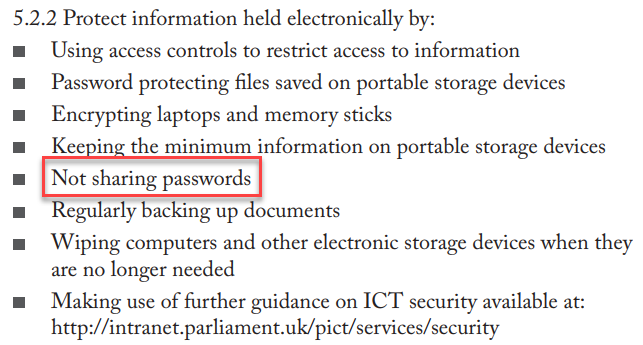

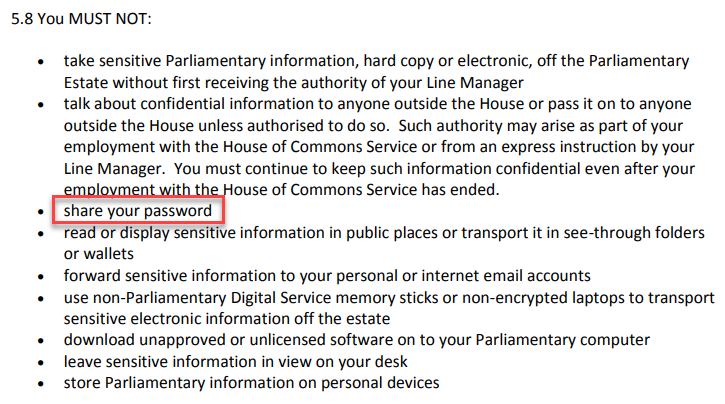

In many organisations, there are very clear conditions of use set out for access to information systems that explicitly prohibit credential sharing. You know, organisations like the British Parliament:

This is from the Advice for Members and their staff document on the UK Parliament Website and at least to my eyes, that seems like pretty explicit advice. Just in case it's not entirely clear, there's also the House of Commons Staff Handbook on Information Security Responsibilities:

There are no accompanying caveats of "but it's alright if it makes things more convenient"! We all know this, not just because you might happen to occasionally read this blog but because we're constantly bombarded with this guidance both online and in the workplace:

Oftentimes, the ramifications of deliberately circumventing security controls designed to protect the organisation can be severe:

I would be fired on the spot if I allowed access to my machine with my details, I would also be fired accessing another machine on their account.

— Sam George (@sam_george) December 3, 2017

As above - this would be a sackable offence in any normal organisation, for exactly this reason.

— tony nog #FBPE (@tony_nog) December 2, 2017

How could you determine the source of a breach if 8 people are using the same login?

Do MPs operate on a different planet?https://t.co/pR6J0zXyQD

If anyone knows what the possible repercussions for a member of parliament violating these policies are, do chime in via the comments section below.

Summary

I'm conscious the tweet that sparked this debate was made on a Saturday evening and for all I know, it could have been an off-handed comment after a bottle of chardonnay while kicking back on the couch. I also appreciate that for non-tech people this may have seemed like a perfectly reasonable approach at the time. A chorus of voices have now set her straight so I'm inclined to put more personal judgement on what happens next as opposed to what might have been nothing more than an uninformed casual comment.

But we do need to call out credential sharing in this fashion for what it is and it's precisely what I highlighted in that original tweet - lack of education. The Register piece I linked to earlier on quoted one MP as saying the following and it's hard not to agree with it in this case:

Most MPs have that fatal combination of arrogance, entitlement and ignorance, which mean they don't think codes of practice are for them

It's alarming to read that Nadine believes criticism of her approach is due to her gender because if ever there was a construct that's entirely gender-unbiased, it's access controls! Giving other people your credentials in a situation such as hers is a bad idea regardless of gender, race, sexuality and any other personal attribute someone may feel discriminated by.

With all of that said, if you're working in an environment where security controls are making it hard for you to do the very job you're employed to do, reach out to your IT department. In many cases there'll be solutions precisely like the delegated access explained above. It's highly likely that in Nadine's case, she can have her cake and eat it too in terms of providing staffers access to information and not breaking fundamental infosec principles.

The great irony of the debates justifying credential sharing is that they were sparked by someone attempting to claim innocence with those supporting him saying "well, it could have been someone else using his credentials"! This is precisely why this is problem! Fortunately, this whole thing was sparked by something as benign as looking at porn and before anyone jumps up and down and says that's actually a serious violation, when you consider the sorts of activities we task those in parliament with, you can see how behaviour under someone's identity we can't attribute back to them could be far, far more serious.

Update

The Information Commissioners Office (ICO) has picked up on politicians sharing their passwords and tweeted about it here:

We’re aware of reports that MPs share logins and passwords and are making enquiries of the relevant parliamentary authorities. We would remind MPs and others of their obligations under the Data Protection Act to keep personal data secure. https://t.co/FLPeP8M7c8

— ICO (@ICOnews) December 4, 2017

The National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) also has some excellent practical guidance about simplifying your approach to passwords which is a good read if it all feels too hard.

It’s now effectively impossible to spend a month following IT (and not just) new and not hear of breaches, “hacks”, or general security fiascos. Some of these are tracked down to very basic mistakes in configuration or coding of software, including the lack of hashing of passwords in database. Everyone in the industry, including me, have at some point expressed the importance of proper QA and testing, and budgeting for them in the development process. But what if the problem is much higher up the chain?

Falsehoods Programmers Believe About Names is now over seven years old, and yet my just barely complicated full name (first name with a space in it, surname with an accent) can’t be easily used by most of the services I routinely use. Ireland was particularly interesting, as most services would support characters in the “Latin extended” alphabet, due to the Irish language use of ó, but they wouldn’t accept my surname, which uses ò — this not a first, I had trouble getting invoices from French companies before because they only know about ó as a character.

In a related, but not directly connected topic, there are the problems an acquaintance of mine keeps stumbling across. They don’t want service providers to attach a title to their account, but it looks like most of the developers that implement account handling don’t actually think about this option at all, and make it hard to not set a honorific at all. In particular, it appears not only UIs tend to include a mandatory drop-down list of titles, but the database schema (or whichever other model is used to store the information) also provides the title as an enumeration within a list — that is apparent by the way my acquaintance has had their account reverted to a “default” value, likely the “zeroth” one in the enumeration.

And since most systems don’t end up using British Airways’s honorific list but are rather limited to the “usual” ones, that appears to be “Ms” more often than not, as it sorts (lexicographically) before the others. I have had that happen to me a couple of times too, as I don’t usually file the “title” field on paper forms (I never seen much of a point of it), and I guess somewhere in the pipeline a model really expects a person to have a title.

All of this has me wondering, oh-so-many times, why most systems appear to want to store a name in separate entries for first and last name (or variation thereof), and why they insist on having a honorific title that is “one of the list” rather than a freeform (which would accept the empty string as a valid value). My theory on this is that it’s the fault of the training, or of the documentation. Multiple tutorials I have read, and even followed, over the years defined a model for a “person” – whether it is an user, customer, or any other entity related to the service itself – and many of these use the most basic identifying information about a person as fields to show how the model works, which give you “name”, “surname”, and “title” fields. Bonus points to use an enumeration for the title rather than a freeform, or validation that the title is one of the “admissible” ones.

You could call this a straw man argument, but the truth is that it didn’t take me any time at all to find an example tutorial (See also Archive.is, as I hope the live version can be fixed!) that did exactly that.

Similarly, I have seen sample tutorial code explaining how to write authentication primitives that oversimplify the procedure by either ignoring the salt-and-hashing or using obviously broken hashing functions such as crypt() rather than anything solid. Given many of us know all too well how even important jobs that are not flashy enough for a “rockstar” can be pushed into the hands of junior developers or even interns, I would not be surprised if a good chunk of these weak authentication problems that are now causing us so much pain are caused by simple bad practices that are (still) taught to those who join our profession.

I am afraid I don’t have an answer of how to fix this situation. While musing, again on Twitter, the only suggestion for a good text on writing correct authentication code is the NIST recommendations, but these are, unsurprisingly, written in a tone that is not useful to teach how to do things. They are standards first and foremost, and they are good, but that makes them extremely unsuitable for newcomers to learn how to do things correctly. And while they do provide very solid ground for building formally correct implementations of common libraries to implement the authentication — I somehow doubt that most systems would care about the formal correctness of their login page, particularly given the stories we have seen up to now.

I have seen comments on social media (different people on different media) about what makes a good source of documentation changes depending on your expertise, which is quite correct. Giving a long list of things that you should or should not do is probably a bad way to introduce newcomers to development in general. But maybe we should make sure that examples, samples, and documentation are updated so that they show the current best practice rather than overly simplified, or artificially complicated (sometimes at the same time) examples.

If you’re writing documentation, or new libraries (because you’re writing documentation for new libraries you write, right?) you may want to make sure that the “minimal” example is actually the minimum you need to do, and not skip over things like error checks, or full initialisation. And please, take a look at the various “Falsehoods Programmers Believe About” lists — and see if your example implementation make those assumptions. And if so fix them, please. You’ll prevent many mistakes from happening in real world applications, simply because the next junior developer who gets hired to build a startup’s latest website will not be steered towards the wrong implementations.

Ever wanted to date your sword? Here you go

We’ve already found our favorite mashup of 2019: Boyfriend Dungeon, a dungeon crawler from indie team Kitfox Games (Moon Hunters, The Shrouded Isle), which combines hack-and-slash gameplay with very, very cute guys and girls.

Boyfriend Dungeon is exactly what it says on the tin, based on the first trailer. Players are a tiny warrior fighting through monster-ridden areas. Scattered across the procedurally generated dungeons are a bunch of lost weapons — which, once rescued, turn out to actually be extremely cute singles.

That’s when the dungeon crawler turns into a romance game, and it’s also when we all realized that Boyfriend Dungeon is something special. Every romance option has their own specific weapon to equip, from an epee to a dagger and then some. Players work to level up those weapons, but also to win over these sweet babes during dialogue scenes. If this isn’t the smartest combination of genres we’ve seen in some time, we don’t know what is.

Oh, and it looks like one of the eligible bachelors is a cat. Put us down for one copy of Boyfriend Dungeon when it launches sometime in 2019, and pay attention to Kitfox Games’ social media channels for development updates.